Digital Transgender Archive

LGB and/or T History

Author: Hugh Ryan

Any line we might try to draw to separate lesbian/gay/bisexual history (LGB) from transgender history (trans) would be imprecise, blurry, and certainly not straight. Because of the incomplete archives we have, attempts to separate histories of sexuality and gender transgression often resort to pure guesswork. Worse, just trying to find that line forces us to consider all of history through two modern categories – gender and sexuality – making it harder to understand the very thing we are researching.

Even in just the last few decades, the meaning of “transgender” has shifted radically. To take one example: in 19 96, Leslie Feinberg’s Transgender Warriors (one of the first popular histories of transgender people) was published with the subtitle “From Joan of Arc to RuPaul.” But today, RuPaul is considered a cisgender drag queen, not a transgender person. This shows how the conversation around transgender history has moved away from focusing on practices that cross gender norms (like drag), and towards focusing on people who self-identify as transgender.

96, Leslie Feinberg’s Transgender Warriors (one of the first popular histories of transgender people) was published with the subtitle “From Joan of Arc to RuPaul.” But today, RuPaul is considered a cisgender drag queen, not a transgender person. This shows how the conversation around transgender history has moved away from focusing on practices that cross gender norms (like drag), and towards focusing on people who self-identify as transgender.

“Transgender” has gone from an umbrella term for different behaviors, to an umbrella term for different identities.

While this is a triumph for self-identification, which allows people to express how they want to be understood regardless of how they might look to an outside viewer, it is not a stable ground from which to conduct historical research. Identity can be invisible, or unstated, and it shifts over time, making it impossible to definitively state the self-identification of people in the past. The importance of self-identification over behavior is, itself, a recent phenomenon worth investigating.

Therefore, we do not see “LGB” and “T” histories as discrete categories; rather, they are a collection of shared roots and overlapping fields of investigation. Many figures have a place in both histories, regardless of what terms they used to describe themselves. How can that be? For several reasons:

· For many people in history, we have no access to their private thoughts about their identity, making it impossible to label them “correctly.”

· Others may have identified in ways that don’t neatly overlap with our current ideas of “lesbian,” “gay,” or “trans.”

· Some may have changed their identification over time, or in different circumstances.

· Still others may have identified as cis and gay, but exhibited behaviors that transgress gender (like the RuPaul example above).

In all of these cases – and many others – it is impossible to separate what is LGB history from what is T history, and vice versa. And the further back in time we go, the less it makes sense to try and separate people into these categories.

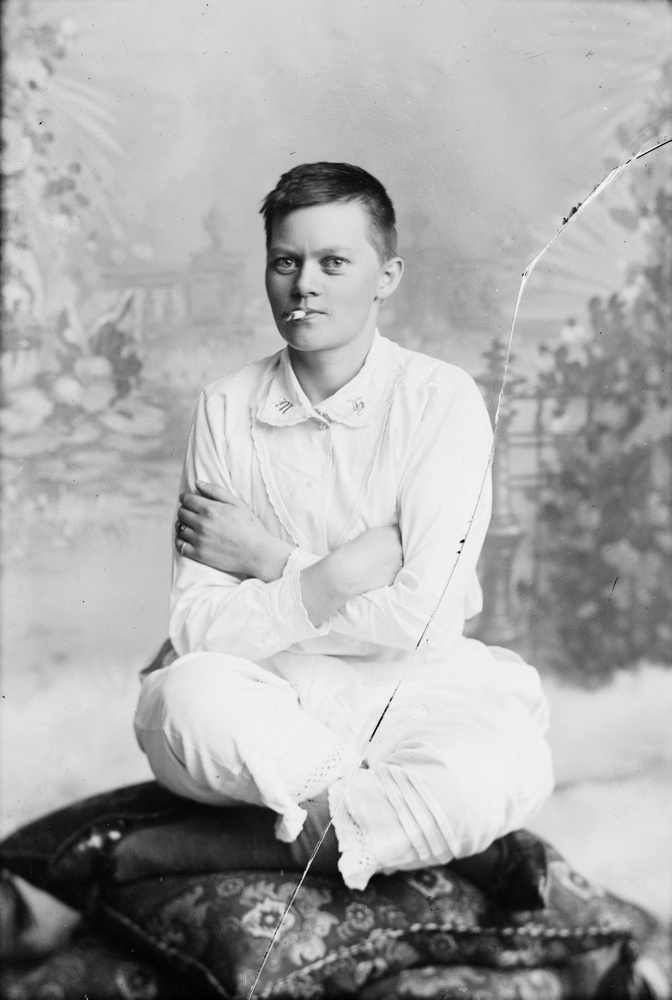

In the 19th century in the United States (and much of Western Europe), sex, sexuality, and gender identity were thought of very differently than we think of them today. Before Sigmund Freud, Americans did not see sexuality as an independent concept around which you could develop a unique identity, such as “gay” or “straight.” Instead, sexual desire and activity were understood as part of your general ability to conform to expectations for your gender. Those who looked, acted, or felt outside the norm for their supposed sex/gender were deemed “inverts” (in reference to their “sexual inversion.”)

This “inversion” was understood as physical, not emotional or mental: people who we today would view as LGBTQ+ were believed to have deviant bodies, more like those of the “opposite” sex. This seems strange to modern people – of course lesbians don’t have inherently masculine bodies. But think about how many traits you have that might be seen as outside the range of your sex: the pattern of your body hair, the shape of your hips, the tenor of your voice, the swing of your stride, etc. For people whose behaviors or desires were outside of the norm for their gender, it was easy to believe that their bodies were outside of the norm for their sex.

This “inversion” was understood as physical, not emotional or mental: people who we today would view as LGBTQ+ were believed to have deviant bodies, more like those of the “opposite” sex. This seems strange to modern people – of course lesbians don’t have inherently masculine bodies. But think about how many traits you have that might be seen as outside the range of your sex: the pattern of your body hair, the shape of your hips, the tenor of your voice, the swing of your stride, etc. For people whose behaviors or desires were outside of the norm for their gender, it was easy to believe that their bodies were outside of the norm for their sex.

For these reasons, most people in the 19th century who understood themselves as queer likely believed they were improperly gendered, or had deviant bodies. Thus, some people who appear to be gender-normative homosexuals to modern people were actually having what they understood to be transgender and/or intersex experiences.

Does that mean it is inappropriate to discuss these people as figures in gay history? Not at all. These individuals are neither gay nor trans, but they are part of both gay and trans history. Just as biology tracks the evolution of organic life from dinosaurs to both lizards and birds, so too do our modern ideas of “L,” “G,” “B,” and “T” share primordial roots in the form of the invert, the “mannish woman,” the fairy, the male impersonator, and many other pre-modern ways of defining folks we today call LGBTQ+.

Our history is materialist and identarian; it encompasses both those who identify as transgender (regardless of the terminology they used), and people whose lived experience transgressed gender (regardless of the terminology they used). We make space in trans history for:

· people who could not verbalize their trans identity,

· people who never encountered words for their gender experience,

· people whose lives (/the public records of their lives) were cut short before they could practice, experience, or acknowledge trans-ness,

· people who understood themselves as crossing gender or having intersex bodies, even if we would not see them that way were they alive today.

· people who never claim – or even actively reject – terms such as “transgender,” but lived lives that complicated, rejected, or in other ways “trans’d” gender.

Rather than take an “either / or” approach to queer and trans history, we push for a “both / and” approach to these histories. We are not trying to detangle these identities – to “prove” that someone was trans or was lesbian, for example. Instead, we embrace multiple explorations as the most accurate representation of a past that will never conform to our modern ways of thinking.

For decades, LGB historians have presented indicators of gender inversion as signs of hidden homosexuality. In doing so, they have erased transgender practices and identities and muddied our understanding of the difference between modern and historical ideas of queerness. This is not an incorrect mode of investigation, but it is a severely limited one, and when it is presented as the only acceptable approach to treating figures in queer history, it severely limits what we can know about our past.

These limits are also true the further we move away from an American/Western-European cultural context. While colonization has spread Western LGBTQ+ ideas around the world, claiming them as applicable to living people everywhere, other ways of understanding queerness are equally valid and may not be compatible with modern American/Western-European categories.

We see transgender history as opening up fresh ground for re-examining all histories of sexuality and gender, including – but never limited to – those people who would identify with our current definition of “trans.” As you explore the DTA, we invite you to reflect on our expansive definition of transgender history, and consider how different historians, authors, and readers bring their own definitions and interpretive frames to this work. What does trans history mean to you, and why?